The History of Astrology in India, Arabia and China

The history of astrology began in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC. But it was a long way from the pure observation of celestial signs to the calculability of planetary movements to the first personal horoscopes, as they emerged in Greece in the 5th century BC. Astrology finally took on its present form in the Roman Empire. Ancient textbooks from the first century AD, such as those by Ptolemy or Manilius, explain the basic elements of the horoscope that are still common today: the zodiac, the planets, the aspects and the houses. Modern astrologers from all over the world still refer to this basic structure. But with the decline of the Roman Empire, astrology fell into oblivion in Europe. However, the old teachings survived in the Arab world and in India.

Sidereal Astrology in India

Astrology had already reached India in the 4th century BC, especially during the conquests of Alexander the Great. It was integrated into the Hindu world view and its traditional lunar astrology. Thus, to this day, the moon plays a much stronger role in Indian astrology (Jyotisa) than in Western astrology. The 27 or 28 lunar stations (nakshatras) through which the moon passes in the course of its cycle were supplemented by the twelve solar signs of the zodiac (rashis) through Hellenistic influences. The ancient Indian solar and lunar calendars were extended by the five planets (Grahas) Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. And the seven-day week associated with the planets (one day each for the sun, moon and the five planets) was introduced. All these influences go back to the Greeks.

In the course of the following centuries, Indian and Western astrology increasingly diverged. One main reason for this is the zodiac. Traditionally, its starting point is at 0° Aries. In the last pre-Christian centuries, the Sun’s entry into the sidereal constellation of Aries was largely identical with the equinox. However, as the Earth’s axis shifts over the centuries (precession), the constellations and the equinoctial points drift further and further apart. About every 2,200 years they shift by one sign. Only after 26,000 years do they coincide again. In western astrology, the tropical zodiac was followed. This means that 0° Aries is defined as the point of the equinox and meanwhile has nothing to do with the constellations in the sky. In Indian astrology, on the other hand, the sidereal zodiac has been retained. 0° Aries is therefore still where the constellation of Aries begins in the sky. However, this day is now more than three weeks after the equinox, so not around 21 March, but around 14 April. A stormy Aries of Western astrology is thus still a dreamy Pisces in India. An eccentric Aquarius according to the tropical zodiac is a conservative Capricorn in the sidereal zodiac.

This contradiction is one of the main arguments of the critics against astrology. And indeed, astrologers are in a state of explanatory emergency here. Some astrologers claim that both the tropical and the sidereal zodiac are coherent and simply represent different levels of the horoscope. However, the question then remains open as to why the same characteristics are assigned to the individual signs of the zodiac in both reference systems. In a comparative analysis of Vedic astrology books, the renowned astro-historian Dieter Koch (*1959) has found that the descriptions of the signs of the zodiac do have some common features. For example, character traits are attributed to the sidereal Scorpio that are associated in the West with the tropical Sagittarius. With the coordinate systems, the areas of meaning have also shifted, so that the contradictions in content are not so serious. However, it becomes problematic with the ruler system. Here, as there, Mars is the planet of Aries, Jupiter the planet of Pisces and so on. A tropical Aries Ascendant is assigned the warlike malefactor Mars as his birth planet, while the same person in India is subject to the great benefactor Jupiter. This contradiction seems insoluble to this day. And so the most popular evasion is that Western astrologers dismiss the sidereal and Indian astrologers dismiss the tropical zodiac as nonsense.

Arabian Astrology

The second cultural area in which ancient astrology lived on was the Arab world. The Arabs preserved the intellectual heritage of the Greeks and developed it further, while Europe sank into the Dark Ages. Among the most famous Arab astrologers were Messallah, who calculated the date for the founding of Baghdad in 762 AD, Sahl ben Bishr, Abu Masar (both in the first half of the 9th century), Albubather (about 875 – 950) and above all the famous polymath Al-Biruni (973 – 1050), as well as Ali ben Ragel (1016 – 1062), one of the most quoted astrologers of the Middle Ages. The great influence that the Arabs had on the development of astrology is still expressed today in the term “Arabic parts”. Although this technique has its origins in antiquity, it was only practised on a large scale by the Arabs. It involves adding or subtracting the planets, the ascendant and the medium coeli (the highest point in the sky). The most prominent of these points is the Part of Fortune. Here the distance from the Sun to the Moon is measured and then subtracted from the Ascendant. The Arabs used hundreds of these parts, and each part could in turn be the starting point for calculating other parts. Al-Biruni names numerous Arabic points such as the following:

Triumph: From the Part of Fortune to Saturn, carried off from the Ascendant.

Mysteries: From the ruler of the Ascendant to the Medium Coeli, ablated from the Ascendant.

Destiny of the Sultan: From MC conjunction Mercury to the MC of the solar progression, ablated from Jupiter

Duration of Employment: From Sun to Saturn, subtracted from Ascendant.

Decapitation: From Moon to Mars, ablated from the cusp of the 8th house

Whether for father, mother, brother, sister, master, slaves, business, torture, profession, celebrity, inheritance, children, love, horsemanship, beauty or quarrel, even for wine, nuts or olives, there was an Arabic part for almost everything. The inflation of astrological interpretation factors already began at that time. There were so many Arabic parts that one could calculate anything and everything at any time, at least in retrospect.

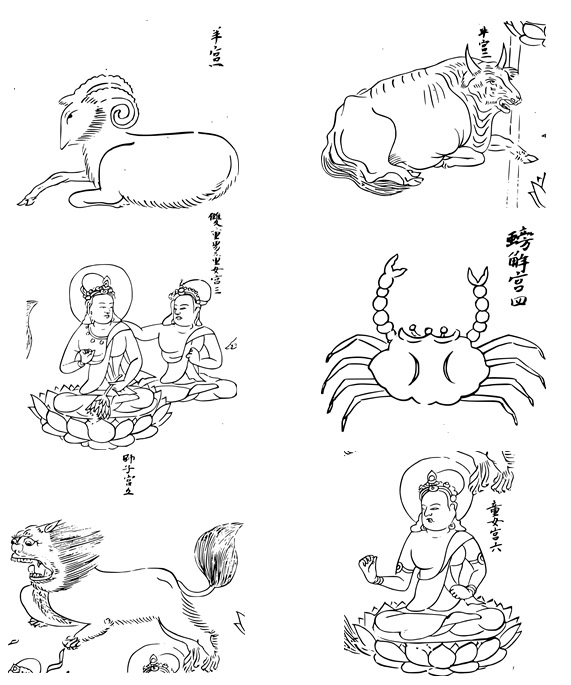

Western Astrology in Persia and China

It was only in the 2000s that researchers discovered that Western astrology had reached China via the Persian Empire, as early as the 8th century AD. The Canadian Tibetologist Jeffrey Kotyk (*1985) showed that in Tang Dynasty China, Persian astronomers worked at the emperor’s court and thus brought Iranian astrology, a mixture of Hellenistic and Indian influences, to East Asia. There it persisted for several centuries as a renowned forecasting discipline. Kotyk has also uncovered a number of fascinating details. For example, 8th century Iranian astrology used not only the Sun, Moon, the five planets and the lunar nodes (dragon’s head and dragon’s tail), but also a factor called Lilith. The orbit of this sinister, dark demoness corresponds to the furthest point of the moon’s orbit from earth (apogee). In modern astrology, this factor was only introduced in the 1960s and became very popular in the 1980s. Both the calculation and the interpretation of the modern Lilith correspond amazingly to the Iranian descriptions, although there is no connection whatsoever between these two lines of tradition. The images and descriptions of the planets and signs of the zodiac also show a great similarity with the Western models.

Despite Western influences, astrology in China was still strongly connected to sign interpretation. The sky was observed and also served visually as a map of destiny. The Milky Way corresponded to the Yellow River, the most prominent stream in the topography of the empire. And above and below the Milky Way, the underlying regions of China north and south of the Yellow River were reflected in the sky. If constellations of planets occurred in these celestial regions, they also affected the corresponding region on earth.

According to the American sinologist David Pankenier (*1946), planetary constellations played a major role here. These were particularly significant when all the planets were gathered in one sign of the zodiac. This only happens about every 517 years. This rare event was seen as a sign that the existing order was undergoing a major upheaval and that the “Heavenly Mandate” (Tianming) could pass to a new ruler. And indeed, there is a surprising number of overthrows and dynastic changes in Chinese history at these major conjunctions. The 1953 BC conjunction heralded the era of the Xia dynasty, the 1576 BC conjunction the reign of the Shang, and the 1059 BC conjunction the rise to power of the Zhou. The conjunctions took place in the celestial regions of the corresponding dynasties. These rare celestial events apparently made such a powerful impression on rulers and subversives that faith moved mountains. One has to imagine the enormous motivating or demoralising effect of such a powerful sign when it is believed by everybody. And so one can be curious about the next great conjunction in September 2040, because such a rare omen could probably also develop a certain pull in modern China.

The original version of this article including all sources can be found in the following book:

Niederwieser, Christof (2020) PROGNOSTIK 03: Trends & Zyklen der Zeit, Rottweil: Zukunftsverlag, S. 114ff